David Wark Griffith, director of 'Intolerance' (1916).

D.W. Griffith has long enjoyed a reputation as the "father of film."

Example: Each year at the

Kansas Silent Film Festival, they show at least one short film of Griffith's to acknowledge his crucial role in motion picture history.

This year, it's no different. For their 20th annual festival next month, the Kansas folks are running 'Those Awful Hats' (1909).

It's a half-reel novelty short, part of Griffith's voluminous Biograph output, when he must have been being paid for his work by the foot.

But it's Griffith, and they

have to include at least one title from "the father of film." (And guess who's doing the music?)

So for a long time, I just thought of Griffith as a kind of 'George Washington' of cinema: there at the beginning, as someone

had to be.

Yeah, he pioneered some new ideas such as close-ups and telling two stories at once and cutting between them. But others did those things, too. What's the big deal?

And the films themselves seemed hopelessly creaky and old-fashioned. Good enough for their time, perhaps, but cinematic technique rapidly moved on, leaving Griffith epics such as 'Way Down East' (1920) and 'Orphans of the Storm' (1922) as quaint relics from an earlier age.

Well—only recently have I come to really understand the crucial role Griffith played in bringing cinema from a novelty to a fully accepted major art form.

And it wasn't about camera angles and fancy editing, although those played a part.

What it was about was

story. Griffith, more than anyone else at the time, really know how to put together a narrative that would grab people's attention and hold it for as long as needed—as much as several hours at a time.

And this, I think, played a huge role in convincing the public and the business community about the power of the motion picture.

How did Griffith learn how to do this? The hard way: by directing third-rate casts in fourth-rate melodramas that toured small town theaters. In these places, you

had to be entertaining or you'd risk getting tarred and feathered.

So prior to his film career, Griffith had the best possible training for cinema: a couple of decades of putting on stage plays to extremely unforgiving audiences. By necessity, he became an expert at understanding how to hook an audience and

keep it hooked.

This is not easy. It involves understanding the at-times unpredictable nature of how crowds behave, which is very different from how an individual may respond to any given situation. It's part mob psychology, part peer pressure, and a fair helping of intuition, I think.

But little by little, Griffith accumulated an expertise in constructing stories that could and would mesmerize a crowd. He probably came to understand it in his bones: how to structure a story so as to capture the crowd's attention and then manipulate it to a fever-pitch of excitement.

And it was this knowledge, more than anything else, that came in handy when it was time to put together films that went beyond the one-reel dramas that were the mainstay of cinema's early years.

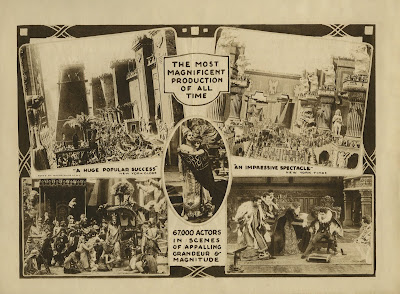

An original poster for 'Intolerance' (1916).

Thanks to his background in theater, Griffith instinctively knew how to lay out a story such as that of 'The Birth of a Nation' so as to work in a crowded theater. He knew how to do this so well, he could do it in the new medium of film, without an audience present.

To his collaborators and to studio executives, it must have seemed like magic. Because for awhile, no one's films sold tickets the way D.W. Griffith's films did. Once he started making "blockbusters" (a term from World War II not in use in Griffith's time), he showed once and for all that it was possible for a motion picture to the be main event of an evening at the theater, rather than just a sideshow novelty.

Today, we can see movies on our own in ways that Griffith wouldn't have imagined: online, on our phones, etc. And. most significantly,

alone. And Griffith's work, I think, suffers more than most because his films were designed from the ground up to excite crowds: the bigger the better! It's that very quality that helped make him the "father of film."

Take away that part of the experience, and you rob much of the reason for why Griffith put together his films the way he did.

One of the best examples of Griffith's ability to excite an audience is 'Intolerance' (1916), his four-stories-in-one tour de force. The film turns 100 this year, and I'll be doing music for several upcoming screenings, starting on Wednesday, Jan. 27 at Merrimack College, North Andover, Mass. (Details in the press release below. I'm also doing it in Wilton, N.H. on Sunday, Jan. 31.)

For a long time, I shied away from accompanying this film, intimidated by its length (three hours!) and thinking of its narrative complexity as something of an over-the-top gimmick ripe for satire, which Buster Keaton produced in his 'Three Ages' of 1923. I had better things to do.

But I programmed it for the first time last year, and it turned out to be a highlight of my efforts as an accompanist. Run in front of an audience, the film leaped to life! And the final 30 minutes, in which all four stories are intercut faster and faster, was one of the most exhilarating experiences I've ever had in a theater.

As the pace picked up, everything happened at just the right moment for maximum impact. Griffith's instincts were rock solid, then as now, and the sequence retains its power even to this day. It was incredible. It was inexorable. And I couldn't take my eyes off the screen!

So

that's why he's known as the 'Father of Film!'

See for yourself by attending one of our upcoming 100th anniversary screenings of 'Intolerance.' More info below on the Jan. 27th screening at Merrimack College.

* * *

Biggest set ever? Ancient Babylon, as reconstructed in southern California for 'Intolerance.'

MONDAY, JAN. 18, 2016 / FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

Contact Jeff Rapsis • (603) 236-9237 • jeffrapsis@gmail.com

At the Rogers Center: With 'Intolerance,'

four stories are better than one

Rarely screened landmark 1916 silent film epic to be shown with live music on Wednesday, Jan. 27 at Merrimack College

ANDOVER, Mass.—It was a breakthrough that changed the movies forever: a three-hour epic knitting together four sweeping stories spanning 2,500 years, all designed to show mankind's struggles and the redeeming power of love throughout human history.

The film was D.W. Griffith's 'Intolerance' (1916), which stunned the movie-going public with its vast scope, enormous sets, large cast, and revolutionary editing. Often named to lists of the 100 best films of all times, critics continue to point to 'Intolerance' as one of the most influential and important milestones of early cinema.

See for yourself with a rare screening of a restored version of 'Intolerance' at the Rogers Center for the Performing Arts at Merrimack College on Wednesday, Jan. 27 at 7 p.m.

The program, the latest in the Rogers Center's silent film series, will be accompanied by live music performed by silent film composer Jeff Rapsis. Admission is free.

In reviving 'Intolerance' and other great films of Hollywood's early years, the Rogers Center aims to show silent movies as they were meant to be seen—in high quality prints, on a large screen, with live music, and with an audience.

"All those elements are important parts of the silent film experience," said Rapsis, who will improvise a live score for 'Intolerance' on the spot. "Recreate those conditions, and the classics of early Hollywood leap back to life. They featured great stories with compelling characters and universal appeal, so it's no surprise that they hold up and we still respond to them."

Rapsis performs on a digital synthesizer that reproduces the texture of the full orchestra and creates a traditional "movie score" sound.

A French poster for a revival of 'Intolerance' (1916).

'Intolerance,' considered one of the great masterpieces of the silent era, intercuts four parallel storylines, each separated by several centuries: A contemporary melodrama of crime and redemption; a Judean story of Christ’s mission and death; a French story about the events surrounding the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre of 1572; and a story depicting the fall of the Babylonian Empire to Persia in 539 BC.

The scenes are linked by shots of a figure representing Eternal Motherhood, rocking a cradle.

Each of the parallel stories are intercut with increasing frequency as the film builds to a climax. The film sets up moral and psychological connections among the different stories.

'Intolerance' was made partly in response to criticism of Griffith's previous film, 'The Birth of a Nation' (1915), which was criticized by the NAACP and other groups as perpetuating racial stereotypes and glorifying the Ku Klux Klan.

One of the unusual characteristics of 'Intolerance' is that many of the characters don't have names. Griffith wished them to be emblematic of human types. Thus, the central female character in the modern story is called The Dear One. Her young husband is called The Boy, and the leader of the local Mafia is called The Musketeer of the Slums.

Because of its four intertwined stories, 'Intolerance' does not feature any one performer in a leading role. However, the enormous cast includes many great names from the silent era, including Lillian Gish, Mae Marsh, Constance Talmadge, Walter Long (a New Hampshire native), and a young Douglas Fairbanks Sr. in an uncredited cameo as a drunken soldier with a monkey.

"This movie was made for the big screen, and this screening at the Rogers Center is a rare chance to see 'Intolerance' the way it was meant to be seen," Rapsis said.

Upcoming feature films in the Rogers Center's silent film series include:

• Wednesday, March 23, 2016, 7 p.m.: 'Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ' (1925) starring Ramon Novarro, Francis X. Bushman. Just in time for Easter! In the Holy Land, a Jewish prince is enslaved by the occupying Romans; inspired by encounters with Jesus, he lives to seek justice. One of the great religious epics of Hollywood's silent film era, including a legendary chariot race that's lost none of its power to thrill.

‘Intolerance' will be shown on Wednesday, Jan. 27 at 7 p.m. at the Rogers Center for the Arts, Merrimack College, 315 North Turnpike St., North Andover, Mass. The program is free and open to the public. For more information, call the Rogers box office at (978) 837-5355. For more info on the music, visit www.jeffrapsis.com.

Vintage promotional materials for 'Intolerance.'